How Tariffs Will Help International Trade

The new Washington is encouraging trade routes that will avoid the U.S.

In the second of my instant reflections on what is happening in Washington at the moment, I offer the present economic analysis.

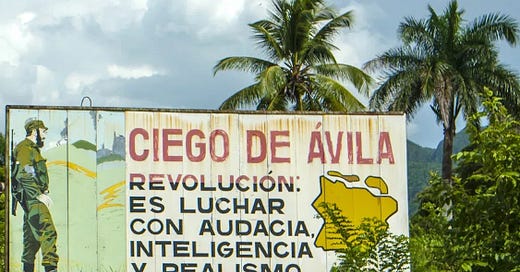

The political situation in the U.S. has so quickly become fraught that it is difficult to tell whether anything in normal life will resemble its current state by the end of this year. I saw this same phenomenon (strange infatuation with the “One Inviolate Leader”) emerge in Cuba before my family left everything in search of a free land. For a brief honeymoon prior to this exodus, Cuba was singing songs of hope and dreams after charismatic Castro took power. Like his American counterpart today, Castro shouted his way to power with bluster, vitriol, anger, and threats - and no actual program of constructive strategic engagement with the wider world.

Because of Castro’s threats, Cuba was soon entirely isolated. It took delivery of free, low-quality Ladas - poor quality Soviet cars - but within two decades, the Soviets’ support disappeared, and Cuba still had no constructive plan of economic engagement. By then, the now-broken Ladas lay lifelessly along Havana’s streets, replaced by new gifts, from China, Cuba’s new friend. These new Ladas were bicycles.

Castro’s regime was the first in Cuban history to rely exclusively on continual defiance, with no message on how to implement the direction of that defiance. Even Khrushchev, the Soviet premier, had an economic plan (based on agricultural reforms) for the USSR. But Cubans were swept away by Castro’s vacuous rhetoric, and, having been mesmerized by its steady incandescence, remained distracted, and failed to put the real task of public administration at Castro’s door. They overlooked the fact that governance has to be the one non negotiable deliverable of any leader; the act of governing institutions is about how to find solutions, not how to foment anger. Cubans turned to Castro for solutions, but ended up only with his anger. Castro came to Havana from the eastern side of the island in 1956, while Batista was still in power, and completed a total overthrow four years later. When the air cleared, Cuba’s citizens found themselves transported to an unrecognizable life in a country that had quietly built a secret police state designed to squelch all modes of dissent and calls for accountability. All institutions were soon living out an uncanny version of the walking dead. Before it all worked out that way, everyone had been sure this would never happen, and being convinced that “it could never happen here” guaranteed that no one saw it coming, while the tone of the speeches kept sucking all the air out of the room. And so, the current invective in Washington rings a most familiar refrain. I've heard this song before. Have you ever been robbed of your future? Of course not — it could never happen here.

And so, the use of defiance as a decoy is an old trick, one that the Washington apparatchiks are now using. To verify this, we need only ask ourselves: what are Americans being asked to actually do amid all this raging lather? Nothing, of course, because the people that the government is supposed to serve are an irrelevant part of the plan; the real enemy is federal government’s own personnel from previous administrations - the accountability system so crucial to a real democracy has been dismantled.

Tilting at windmills is the job of the little guy, the underdog. In that sense, while Cuba’s relationship with anger was completely misguided, it was in some ways commendable: it was a tiny standalone stalwart in a world of two superpower adversaries.

Today’s situation, however, is in so many ways the opposite of that scenario, and, oddly, this is all to the good. Let us take American tariffs — just enacted today — which are a kind of nuclear threat to any country doing business with the U.S. Most people don’t realize that Mexico is the U.S.’s largest trading partner, so these tariffs are a stab in the heart of a major relationship. Regardless the perceived grievances that may motivate them, however, they are, as I will show next, completely self-harming to Americans.

Firstly, all tariffs levied against any country today come with instant reverse tariff directives from the opposite trading partner. This is just problematic when the relationship is “economically monogamous” in the sense that all benefits and difficulties remain locked within a two-country arrangement or relationship. When one partner “attacks” or retaliates against another, the effect is maximally felt by one of the two partners.

The solution for all the southern countries, therefore, is to diversify maximally with each other and with the largest remaining trading partners. In this case, China is more than ready at the moment. If Mexico has 25% tariffs with the U.S. and China 10% (both true as of today), then a Mexico-China relationship saves a total of 35% on two-way trade. At 35%, the savings are sufficient to warrant some quick phone calls, which are already being made, in order to reduce trade with the U.S. and make up the difference with other countries. In the next four years, this pattern will grow, with the U.S. share of global trade diminishing, as former partners establish higher free trade relationships with each other.

But lessened trade with the U.S. is not the worst part of this outcome for American businesses. Naturally, American businesses will also lose trading partners, who will make up the slack by trading around American tariff hurdles. Eight years ago, we saw this happen in the first administration by the present White House occupant, and in one of my own businesses, prices increased overnight - a bad sign - but supplies disappeared, and this really hurt local businesses. A business can operate with lower profit margins due to import tariffs, but it cannot operate if it does not receive goods. Inevitably, this fate again awaits businesses in the U.S., and here is why: if a foreign supplier can sell his goods to a new trading partner who trades without a 25% tariff, it can retain the same level of revenue with that new partner even with a 25% lower amount of trade. The logic for non-American trade is extremely compelling: every business can take a 25% loss of trade if its revenue remains the same. Meanwhile, Americans will pay 25% higher prices on products —if they can find them — that have been subjected to counter-tariffs, and supplies will dwindle gradually as foreign trade accelerates its trade with non-American markets. At the same time, American exports will also lessen, because by avoiding trade with the U.S., foreign countries will buy and sell the same products, tariff-free, from other trading partners, no doubt led by China and the European Union. Inevitably, American businesses which depend on exports will suffer.

Unsentimentally, all of this is great news for the robustness of the global economy, despite being bad news for U.S. trade. The lesson, obviously, is that it’s not 1980 any longer. That world has disappeared, never to return again. Global economic diversification has already brought healthy competition, more choices, and - importantly - a world free from trade extortion.

Now let us put a specific picture on what will happen. Namely, how does greater global economic balance result from the threat of tariffs?

The United States serves as the primary trading partner for several countries, particularly its neighbors and key allies. Based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The U.S. is Canada’s largest trading partner, with significant bilateral trade in goods and services. Mexico, too, engages in extensive trade with the U.S., making it Mexico’s primary trading partner. After this, in order of decreasing trade, other key partners are Japan, Germany, United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Korea, South, Netherlands, Brazil, France, Singapore, Belgium, Taiwan, and Switzerland.

No Ministry of Finance in any country potentially affected by the new American trend of “trade rage” has failed to ponder what is happening: the unity of the economic family is being directly threatened at a time when that landscape is much richer for all countries than it has ever been. Historically, all of the countries with whom the U.S. does heavy trade have forged deep reliance on American trade because the U.S. had brought military security during a period when no other competing countries had built any infrastructure capable of sustaining large-scale, reliable export economies. Let’s see who the international economic players of the 1960s to the 1980s were, when these special relationships developed. The USSR, for example, had a large military but an incredibly disorganized trade bureaucracy focused on its own Communist republics. China was not an economic player before 1984. The primary foreign-trade country, after the U.S., was Germany — specifically West Germany before German unification took place.

As the preceding global trade history chart shows, for any country wanting a strategic ladder to political and economic growth even as late as 1990, America was the only game in town. In 2025, that is no longer the case, as becomes evident once we factor the second most important trading partner for each of these countries. Averaging total trade volume, exports, and imports, consider this matrix and see if you can discern the pattern:

Japan: The United States is Japan's second-largest trading partner, following China.

Germany: France is Germany's second-largest trading partner, after the Netherlands.

United Kingdom: Germany is the UK's second-largest trading partner, following the United States.

Hong Kong: The United States is Hong Kong's second-largest trading partner, after China.

South Korea: The United States is South Korea's second-largest trading partner, following China.

Netherlands: Germany is the Netherlands' second-largest trading partner, after Belgium.

Brazil: The United States is Brazil's second-largest trading partner, following China.

France: Germany is France's second-largest trading partner, after Italy.

Singapore: Malaysia is Singapore's second-largest trading partner, following China.

Belgium: France is Belgium's second-largest trading partner, after the Netherlands.

Taiwan: The United States is Taiwan's second-largest trading partner, following China.

Switzerland: The United States is Switzerland's second-largest trading partner, after Germany.

It is possible to convert the above web of relationships into a graph of first- and second-partner rankings, assigning a .5 score to the second-most-important trading partner and 1 to the most-important-trading partner for each country:

With this compression of data, we have transposed the economic relationships into a simple rank value — Japan’s primary trading partner is China, followed by the US, hence it would assign a “1” value under the China column, and a “.5” under the U.S. column. Assigning a rank for each country’s first- and second-most important trading partner onto the grid, we can then add the “sum relationship value” at the bottom, representing how important each country is to the overall community.

If we assign the value .25 to the third-largest trading partner, each country in the first column will assign a 1, .5, or .25 to its first-, second-, and third-largest trading partner, and this now becomes the relationship matrix:

In a tariff scenario, several countries would be directly affected, primarily countries that are members of NATO or the European Union, and in the likely near future, Hong Kong in retaliation for being part of China. To be charitable, we will leave the UK and Taiwan intact, owing to (still) friendly relations with these two non-aligned bodies.

In this new milieu of the “surprise Blitzkrieg American tariff offensive,” countries will immediately perceive a the U.S. partnership as a potential economic threat (even if tariffs were not yet imposed) and will now react against the trading impasse by moving to strengthen ties with other potential trading partners. The logical scenario is that countries will bolster trading with their next-highest trading partners. Since these relationships are already forged, increased trade will, despite lower initial trade volume, grow to levels that work for each economy. The removal of the U.S. as a dependable trading partner, indicated by the removal of the partner rank in the red cells below, will therefore assign the value in the U.S. rank equally to the other closest partners, increasing their score (as shown in the green cells). This is now the adjusted scenario in which tariff-threatened countries would increase trade with their closer partners:

Before the tariff threat, the US ranked 5.5 against China’s 8.25 as a favored trading partner of this international community. After the threats of tariffs, and assuming that the economic relationships will be bolstered within two years, the new rank for the US will lower to 3.25, China will increase to 10, and Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, and Japan will enjoy greater economic ties with other countries. There is no scenario under which U.S.-threatened tariffs benefit the U.S. in the long run, unless a country fails to diversity with its partners - which it makes sense to do.

Imagine if in your neighborhood, you have a neighbor who threatens the community. He is powerful, but immediately, all neighbors begin to talk amongst themselves and formulate a response that avoids interacting with the bad neighbor. This prudent strategy bolsters the robustness of all neighbors without forcing any one of them to confront the bad neighbor directly. It is inevitable that this will happen under the “economic extortion campaign” that these countries are currently facing.

The broadest benefit here, which I mentioned earlier, is the resulting level of larger, more sincere competition not merely for dominance, but for relationships among each of the community members. When these countries reduce their dependence on American trade, the U.S. loses its bully power.

This is all great news primarily but not exclusively for China, which stands to increase trade with all U.S.-targeted pariahs, and unlike many other countries, China’s economic infrastructure is completely aligned with its military and political institutions, and is capable of doing large-scale volume trade with any country. At a time when the U.S. is assuming a hostile posture with its established relationships, China is extending a glad hand by providing new incentives for trade and building projects in every country of the Western hemisphere. I look forward to a world of richer partnerships for greater good, not of economic controls coerced by one government, even if it is the U.S. And so, the American decisions to strengthen its own place in the world economy will create interest in and partnerships with China instead, as well as among other European countries. And for its own part, the broad economic choices that the world now has will naturally lead to isolation of any unfriendly neighbor. Cuba learned this lesson when it went from being the second largest exporter of sugar in the planet to a complete non player. According to recent data from the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, Cuba currently provides around 0.19% of the world's sugar supply. This happens because once new trade routes and partnerships are established, they replace difficult, conflictive ones.

And it didn't only happen in Cuba. Several countries with historically stable foreign trade have seen their trade diminish or disappear entirely due to changes in government that led to difficult foreign trade relationships. None of them were able to restore their earlier level of trade after healthier alternative relationships were established.

Venezuela is a signal case study. After Hugo Chávez (1999-2013) and Nicolás Maduro (2013-Present) nationalized several industries, particularly oil, mismanagement and reduced production ensued. U.S. and EU sanctions in response to human rights abuses and authoritarian policies severely restricted Venezuela's ability to trade. Once a major oil exporter, Venezuela’s oil exports plummeted as foreign investment withdrew. Similarly, after 1979, Iran, once a major oil supplier to the West, lost most of its Western markets.

Following the 1953 Korean War, North Korea pursued isolationist economic policies (Juche), which led to minimal foreign trade. Sanctions over nuclear weapons development further restricted trade, and North Korea became almost entirely dependent on China for trade. Nearby, after Myanmar’s military coup in 2021 overthrew the democratically elected government, international sanctions followed, leading to diminished foreign investment and trade, particularly with Western nations. Many multinational companies withdrew operations, significantly affecting the economy. Again, in Zimbabwe during the 2000s, Robert Mugabe’s land reform program directed seizures of white-owned farms, which caused agricultural collapse, further reducing exports of tobacco and other crops. And again, international sanctions further reduced trade with Western nations. The Zimbabwe economy spiraled into hyperinflation, and trade collapsed. And lately, as well, after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine under Vladimir Putin, Western nations imposed unprecedented sanctions, cutting Russia off from key financial and trade systems; major Western corporations exited the Russian market, and exports of oil, gas, and other commodities to Europe dropped sharply.

In each of these cases, one country's internal policies caused its partners to become convinced of new options; in each case, there was a pivot, with trade partnerships shifting towards China, India, and other Asian nations. And this can happen without sanctions; merely finding substitute partnerships will have the same effect. It would be a shift that Americans will not see unfolding as U.S. democratic controls are swept away. “It can never happen here” will continue to be heard, until it happens here. The ingredients are all in place, and mixture is rich enough. Watch China and India primarily, for a speedy rise in global trade statistics — those new partnerships will trace a pattern emerging from Western Europe, Canada, and Mexico.

Hopefully I will presently return to my other interests now, and thank you for your time and thoughts. My next article will be on a new film, now almost completed, looking back more than 40,000 years into our past.